-

The electro-intensive industry could become one of the key arguments for keeping nuclear plants running.

-

According to El Economista, the Ministry for the Ecological Transition may be considering extending nuclear production cycles to link part of their output to heavy industry.

April 11, 2025

Last Monday, the newspaper El Economista raised a question that has gone largely unnoticed by public opinion. The financial paper reported rumors that Minister Sara Aagesen’s department might be considering extending the production cycles of nuclear power plants to link part of their output to the electro-intensive industry and vulnerable customers. Beyond the technical feasibility of this idea, the push to delay nuclear shutdowns is increasingly backed by business groups such as the Catalan employers’ association Foment del Treball.

Rather than a solution, the proposal—if true and implemented—has at least two interpretations. On one hand, it might be a move by the government to justify keeping the plants open in the name of a “common good.” A new narrative enters the stage: one in which the industry (specifically, electro-intensive) and vulnerable families are given priority. Who could deny these two groups access to electricity?

However, let’s not forget that, technically, it’s impossible to guarantee that the electron powering a turbine in a Catalan factory comes from the Vandellós nuclear plant, a photovoltaic plant in Lleida, or a reservoir in Sau. Therefore, a sort of nuclear PPA with a guarantee of origin would be needed to certify that the electron is nuclear: carbon-free, but also not renewable.

Nuclear and electro-intensive industries: a marriage of convenience… until other technologies do them apart?

This idea aligns with the recent Draghi Report, which highlights “extending the production cycle of existing reactor fleets to maintain low-carbon supply” as one of three key nuclear action areas. Meanwhile, Spain’s current electricity system has already shown its fragilities: Red Eléctrica has requested temporary shutdowns of electro-intensive industries on several occasions to avoid grid collapse. In this context, one must ask: how can Spain remain industrially competitive if its biggest energy consumers can’t even plug in?

The debate becomes even more relevant considering the exponential increase in electricity demand due to data centers and the development of Artificial Intelligence in Spain, where energy, land, and data converge. Without a reliable and sufficient generation base, we risk squandering this historic opportunity.

Thus, the idea of extending nuclear plant lifespans emerges as a short-term fix, always within the framework of safety and planned oversight. That said, any nuclear extension must be accompanied by an accelerated rollout of alternatives. As Beatriz Corredor, president of Red Eléctrica, warned: “Nuclear shutdowns must go hand-in-hand with the installation of other technologies that balance the system.” Referencing the movie title, Corredor stated the process must be addressed holistically: “everything, everywhere, all at once.” So, the goal isn’t to slow decarbonization, but to sync it with reality: without a diverse and sufficient mix, the system operator will again issue warnings of instability.

Thus, the idea of extending nuclear plant lifespans emerges as a short-term fix, always within the framework of safety and planned oversight. That said, any nuclear extension must be accompanied by an accelerated rollout of alternatives. As Beatriz Corredor, president of Red Eléctrica, warned: “Nuclear shutdowns must go hand-in-hand with the installation of other technologies that balance the system.” Referencing the movie title, Corredor stated the process must be addressed holistically: “everything, everywhere, all at once.” So, the goal isn’t to slow decarbonization, but to sync it with reality: without a diverse and sufficient mix, the system operator will again issue warnings of instability.

The veterans may remember those buttons and stickers with a smiling sun saying “Nuclear? No thanks.” But in light of today’s challenges, the message might evolve into: “Nuclear for industry? Yes, please,” as a rationale for maintaining some nuclear plants. With rising electricity demand and electro-intensive industry at risk, the debate over nuclear continuity takes on new meaning.

Nuclear cartography must reflect the industrial map

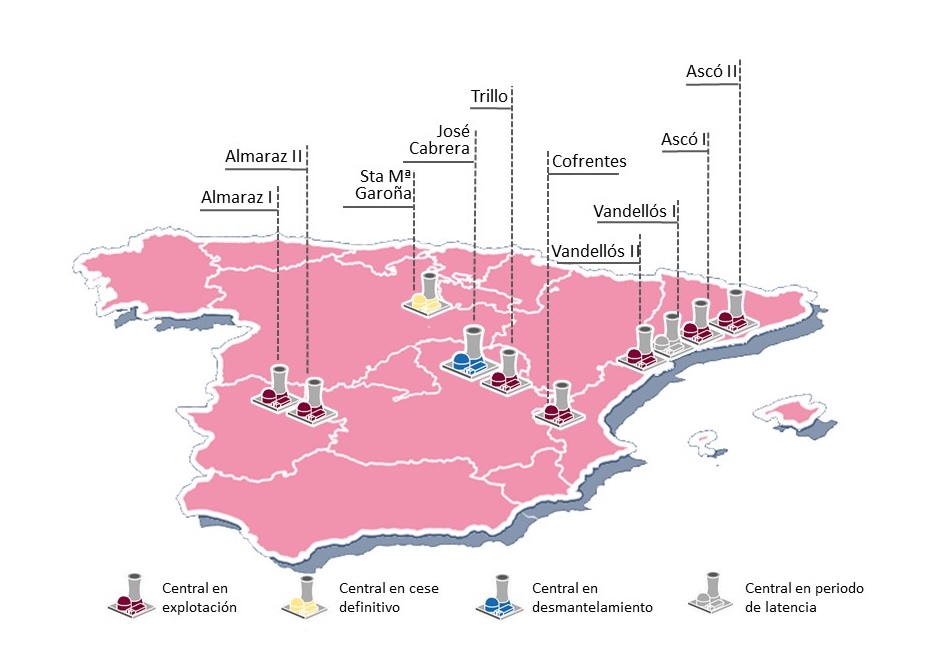

Nuclear planning in Spain can’t be approached uniformly, as electricity production and consumption vary across regions—so do the energy needs of their industries. Currently, only four autonomous communities generate nuclear power (Extremadura, Castilla-La Mancha, Catalonia, and the Valencian Community), but its impact goes beyond regional borders. Some need it for self-sufficiency, others to supply power elsewhere.

Image source: Ministry for the Ecological Transition and the Demographic Challenge

According to Juan Francisco Caro, director of Opina 360, “There are regions where nuclear is essential for industry.” A prime example is Catalonia, where nuclear energy not only covers much of local electricity demand but also supports its industrial fabric. According to the Q4 and full-year 2024 capacity and generation report by Opina 360, nuclear provided 59.1% of the region’s electricity. Additionally, analysis from Foro Industria y Energía—based on Opina 360 data—shows that Catalonia’s industry consumed over a third (34.5%) of the community’s total electricity, underscoring the critical reliance on this source to maintain competitiveness. Caro also notes that “there are regions whose nuclear output directly impacts other autonomous communities.” A clear example is Madrid, which partly relies on electricity generated at the Almaraz nuclear plant (Extremadura) to meet its demand. In fact, according to the industrial electricity consumption report by Foro Industria y Energía, Madrid’s industry consumed 24.9% of the region’s electricity.

This picture shows that energy planning must take into account each region’s industrial demand, territorial interdependencies, and the possibility of adapting the nuclear shutdown schedule and alternative technology deployment to the industrial needs of each area—ensuring both supply and competitiveness. Heavy industry in the Basque Country, chemical production in Tarragona, or steelmaking in Asturias cannot be subjected to uniform criteria; each territory requires tailored solutions based on its energy mix and production structure. A centralist model would not only jeopardize local economies, but also ignore systemic asymmetries. The key lies in mapping real needs—both in generation and consumption—to avoid imbalances that could compromise system security or industrial competitiveness.

The Nuclear Moratorium: A Necessary Patch?

In this debate, the possibility of a moratorium emerges as an option worth considering. It’s not about slowing down the energy transition process, but rather aligning it with the system’s reality and the needs of industry. The urgent priority is to guarantee a stable and secure supply, avoiding rushed decisions that could compromise the country’s competitiveness and energy security.

Ultimately, the discussion around nuclear power cannot be framed in isolation. It is one more piece in the complex machinery of the energy transition. The key lies in balancing the energy trilemma — security, affordability, and sustainability — while integrating solutions that ensure both decarbonization and industrial competitiveness.