April 25, 2025

-

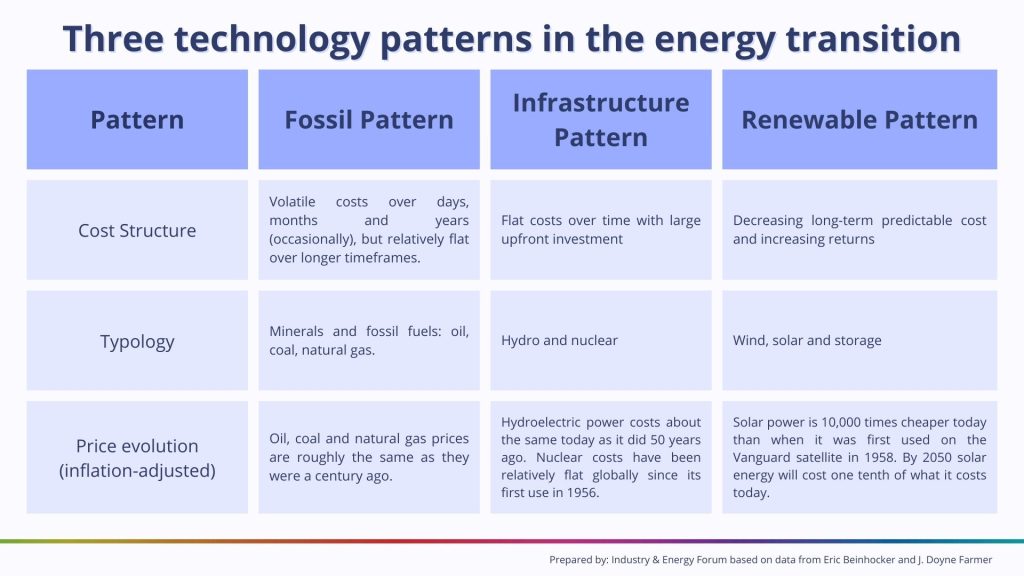

According to two professors from the University of Oxford, the adoption of renewable energy follows the pattern of the so-called S curve, a common pattern of growth and adoption of new technologies.

-

Based on their analysis of the evolution of different patterns in terms of costs and the deployment of new technologies, the two experts believe that even Trump’s policies cannot stop the clean energy revolution.

-

In the industrial environment, we cannot simply estimate the cost of energy for the coming year; we must be able to analyze its evolution to plan for the medium and long term. And for that, studies like these are needed. The industry needs, above all, certainties,” Albert Concepción, director of Foro Industria y Energía.

Madrid, April 25, 2024. At the end of February, University of Oxford professors Eric Beinhocker and J. Doyne Farmer published an article in the Wall Street Journal claiming that Donald Trump’s policies may “marginally slow down progress in the U.S. and damage the competitiveness of American companies, but they cannot stop the fundamental dynamics of technological change nor save a fossil fuel industry that will inevitably shrink drastically in the next two decades.”

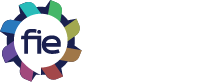

The two experts assert firmly that “the clean energy revolution is being driven by fundamental technological and economic forces that are too strong to be stopped,” based on their analysis of the evolution of different patterns in terms of costs and deployment of new technologies. From the Foro Industria y Energía, we might dare to rename these patterns as fossil, infrastructure, and renewable patterns.

Basically, there are three patterns of technologies:

For these two Oxford experts, the adoption of clean energies, such as solar, wind, or batteries, follows the pattern of what is called an “S curve”: when a technology is new, it grows exponentially but its share is minuscule, so its growth seems almost flat. As the exponential growth continues, its share becomes suddenly large, making its absolute growth also large, until the market saturates, and growth begins to flatten.

Both analysts believe that the adoption rates of renewable energy technologies have been underestimated and their costs have been overestimated, not considering that technological change is not linear, but exponential. They cite the example of mobile phones in the U.S. A new technology is small for a long time, but then suddenly takes off. In 2000, 95% of U.S. households had a landline. By 2023, 75% do not have a landline and only have a mobile. In twenty years, a century-old industry has almost disappeared.

What can we infer from this analysis from the perspective of the industry? First, confirmation, at least from the technical-scientific (academic) perspective, and in case we didn’t have it completely clear yet, that the process is unstoppable and, therefore, the industry must adapt.

Second, since energy costs, as we’ve been emphasizing at Foro Industria y Energía for a long time, are, and will be even more, a fundamental element for industrial development, it is essential to have tools that allow us to anticipate how they will evolve in the medium and long term. In this evolution, the source of energy will play a key role, even beyond whether it is sustainable or not, and will profoundly influence the productive model we can build.

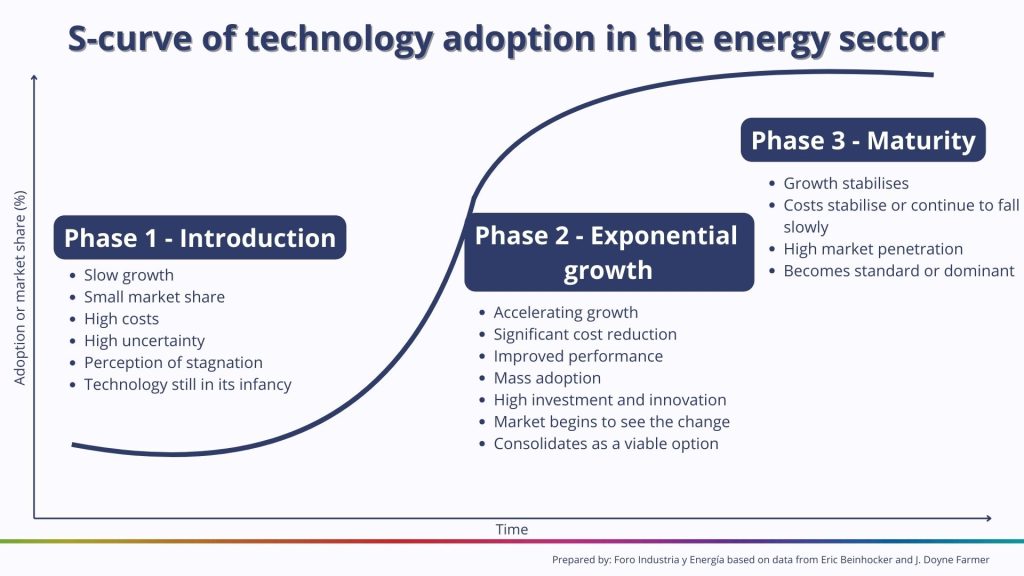

Historical costs and production of main energy supply technologies – Source of the chart: Empirically grounded technology forecasts and the energy transition (Rupert Way, Matthew C. Ives, Penny Mealy & J. Doyne Farmer)

Current analyses help us understand the recent evolution of prices, but they are not enough. The industry needs certainties, and those certainties can only be built with prospective studies that allow us to anticipate scenarios of stability or risk. Today, we almost take for granted that renewables will lower electricity costs, but will that really be the case? To what extent and within what time frames? Strategic decisions of the industrial fabric cannot rely only on short-term projections, but on frameworks that allow guiding development with a more ambitious vision.

As Albert Concepción, director of Foro Industria y Energía, reminds us, “In the industrial environment, we cannot simply estimate the cost of energy for the coming year; we must be able to analyze its evolution to plan for the medium and long term. And for that, studies like these are needed. The industry needs, above all, certainties.” Because energy prices are not just another variable: they are a key constraint. They directly influence the type of technologies developed, the location of investments, and the economic viability of projects. Knowing, for example, what the future cost of certain energy sources or vectors, like hydrogen, batteries, or heat pumps, will be, can be decisive when prioritizing one solution over another.

It is hard to know where we are on the S curve right now, but the S curve seems unstoppable in renewables, and we would be wrong not to heed the warning from the girl from the curve and not have the foresight and vision to take it appropriately. We wouldn’t want the legend of that girl who was hitchhiking to warn us of the risk to be true.

Explanation of the “Girl from the Curve”

The “Girl from the Curve” is a symbolic figure in Spain, referring to a popular metaphor used in Spanish discourse to represent an individual who warns others about the dangers of resisting inevitable change. In this case, the “Girl from the S Curve” represents a metaphorical figure who serves as a cautionary reminder about the unstoppable rise of clean energy technologies, which follow an “S curve” of adoption (slow growth at first, followed by rapid expansion, and then eventual saturation). This figure is not a literal person but symbolizes the warning that the energy transition is inevitable and should be embraced. The “girl” is likened to a hitchhiker, someone on the side of the road trying to warn others about the risks of ignoring this fundamental shift. Her message is clear: the change is coming, and ignoring it could have consequences.

In a sense, the “Girl from the S Curve” can be compared to similar metaphors in English, such as the canary in the coal mine—a figure who warns of an impending shift or danger—or being ahead of the curve, someone who perceives trends before they fully emerge. Just as the canary warned miners of danger, the girl warns us that clean energy is the future, and resisting this change is not an option.