April 30, 2025

-

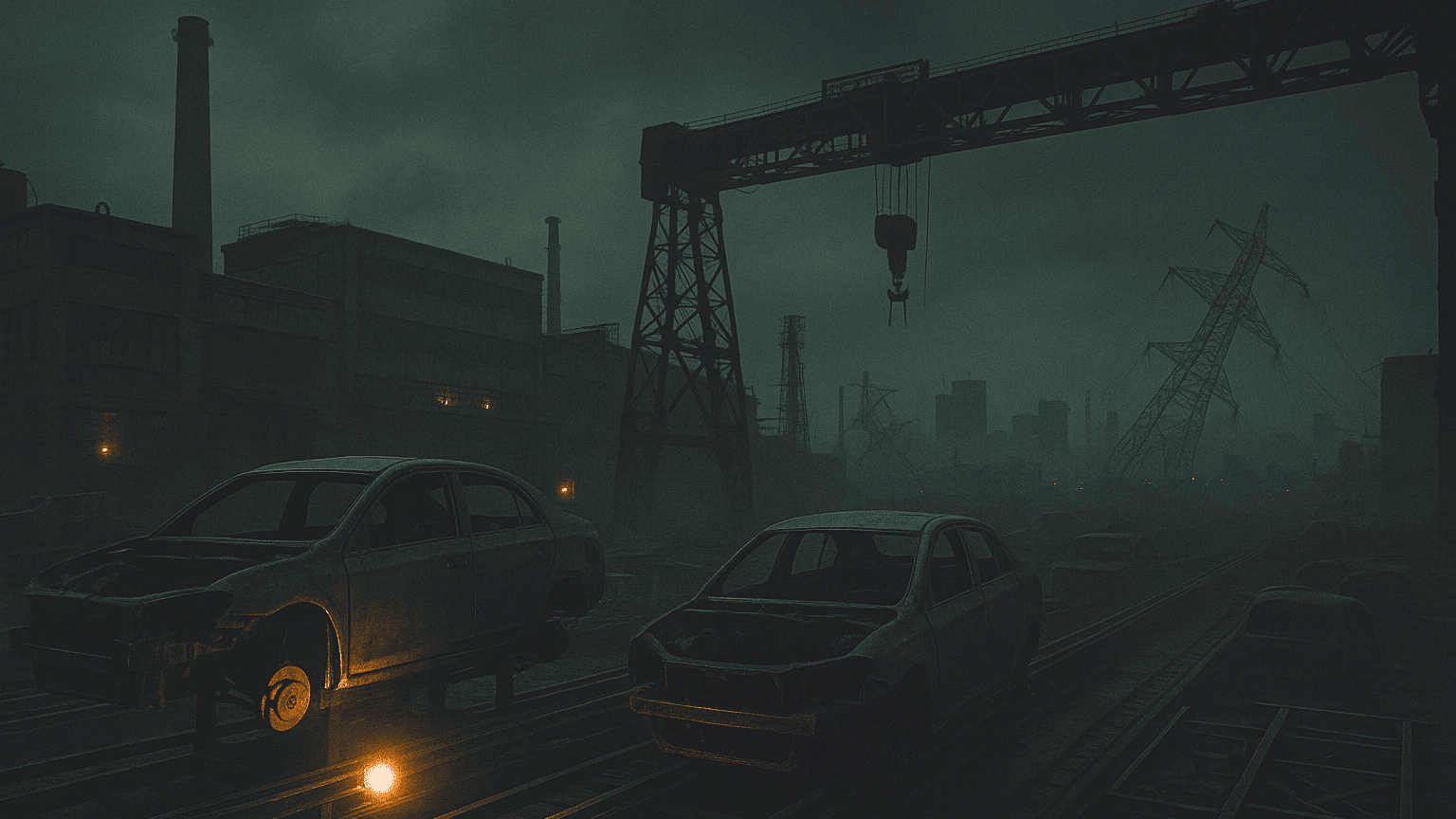

When an entire country loses electricity, it’s not just the assembly lines that stop: doubt also creeps into the industrial sector.

-

The energy transition doesn’t happen in a controlled laboratory: climatic, geopolitical, and technical factors interact in unpredictable ways.

-

Electrification is unstoppable, but its success will depend on how we manage its shadows.

Last week, we dedicated our reflection to uncertainty as a structural condition of the present. We talked about the urgent need for solid medium- and long-term foresight analysis so that the industrial fabric can make informed decisions today, in an environment that changes faster than investment or adaptation cycles allow. Just a few days later, that uncertainty ceased to be an abstraction and became tangible: a widespread blackout affected the entire Iberian Peninsula, plunging homes, services, and, critically, the industry into darkness for hours.

This event, beyond its technical implications, has sparked an urgent debate: are we moving towards resilient electrification necessary for decarbonization, or are we building a fragile dependence, a kind of “electrifixation” that ties us to a vulnerable system? With the sudden disappearance of 15 GW of generation, the system collapse exposed the vulnerabilities of our electrical grid and reignited latent doubts about our readiness for an energy transition almost exclusively focused on electrons.

From Foro Industria y Energía, we maintain that electrification is an unavoidable path, but its success depends on how we manage its risks, learn from its failures, and turn uncertainty into opportunity. This blackout does not invalidate electrification, but it does expose an uncomfortable truth: no system, no matter how innovative, can rest on a single pillar. Recent events have turned this reflection into an urgent warning.

Beyond the technical: the fracture of trust

The effects of this blackout go beyond the technical. There is a psychological and social dimension that should not be underestimated. When an entire country loses electricity, it’s not just the assembly lines that stop: doubt also creeps into the industrial sector. Trust erodes. And that distrust reaches not only infrastructures but also the very narrative of energy transition. Electrification can cease to be perceived as a clean and infallible solution and begin to be seen as yet another dependence, a potential source of fragility.

Although distrust and uncertainty already existed beforehand, large-scale phenomena like yesterday’s blackout act as amplifiers. They can multiply distrust, exacerbate skepticism, and sow doubts about the electrification process as a whole.

Let’s not let the electron walk alone

We live in an era of paradoxes. On one hand, electrification advances as a key solution to decarbonize industry and meet climate goals. On the other, phenomena like the blackout reveal that its implementation is not without risks. The energy transition doesn’t happen in a controlled laboratory: climatic, geopolitical, and technical factors interact in unpredictable ways.

Here lies the first lesson: electrification cannot be a self-sufficient monolith. It needs to rely on complementary systems, redundancies, storage, technical backup, and planning that accounts for extreme scenarios. In a previous article, we already warned about this with a simple but powerful image: “the electron cannot walk alone.” This idea, which may have sounded theoretical before, now resonates with the force of recent experience.

Therefore, it’s not about questioning electrification as a path. It would be a mistake to abandon a necessary process. But it would be equally wrong to embrace it without critical sense, without addressing its limitations or anticipating its vulnerabilities. Electrifying cannot be synonymous with concentrating risks: it must mean intelligent diversification, adaptability, and a systemic vision.

The blow to industry

The impact of the blackout has been especially severe in the industrial sector. Media such as El Mundo and El Economista have highlighted how industries were forced to immediately suspend their activity due to the lack of electricity supply. The impact of this interruption, although still unquantifiable in economic terms, was immediate and significant.

Refineries like Petronor or Repsol activated emergency protocols due to the interruption. Automotive plants such as Ford, Volkswagen, Seat, and Stellantis stopped their production lines, while facilities like Alcoa in San Ciprián are facing complex and costly restart processes. Only a few industries, such as those in Mondragón or CAF, were able to maintain activity thanks to their own generators. But the message is clear: the industry has received a warning about the consequences of excessive dependence.

These cases are not anecdotal. They reflect two structural vulnerabilities. First, most industries lack scalable backup systems. Second, the costs of interruption go beyond lost production: they damage reputations, scare off investments, and erode trust in the stability of the system. Industry cannot afford to be held hostage by recurring electrical failures. It needs solutions that combine electrification with autonomy.

Gray swans on our energy horizon

The black swan theory, popularized by Nassim Taleb, describes highly improbable, high-impact events that, once they occur, seem predictable in retrospect. Was this blackout a black swan? The answer is nuanced. While the magnitude was unexpected, the vulnerabilities of the system were known. It cannot be said that we were blind to the risks of an electrification without a parachute.

Perhaps we are facing a gray swan: a rare event, but plausible and, above all, manageable if measures had been taken in advance. Precisely for this reason, we need to strengthen foresight analysis. We need to turn knowledge into action: anticipate scenarios, diversify solutions, and strengthen system resilience before the improbable becomes inevitable.

What matters now is not classifying the event but how we transform these “gray swans” into opportunities to strengthen our system. It’s not about abandoning electrification, but about complementing it with solutions that mitigate its structural vulnerabilities.

From vulnerability to opportunity: electrifying with resilience

Electrification should not be questioned as a principle, but it should be questioned as a process. The blackout has been a stark reminder of our interdependence and vulnerability. The task is now clear: industry and the energy sector must learn from what happened, reevaluate risks, and work with determination to build a more robust, diversified, and resilient energy system. One that accompanies the electron on its journey toward decarbonization without compromising the supply certainty that our economy and society demand.

Precisely because we believe in electrification as a central vector of the energy transition, we must be the first to identify and address its weak points. Electrification remains the path, but it’s time to ensure that it’s well-paved. What happened should not be interpreted as a reason to halt its progress, but as an imperative to reinforce it. The transformation of our energy model is too important to leave it in the hands of improvisation or blind faith in a single vector. We need planning, foresight, and, above all, humility to recognize that even the best systems can fail.

From Foro Industria y Energía, we will continue to bet on electrification as one of the pillars of decarbonization, but with our eyes wide open. Because the energy transition cannot afford black swans. Our challenge is to turn uncertainties into certainties and gray swans into opportunities. To achieve this, we need rigorous foresight analysis, not as academic exercises, but as real decision-making tools. Electrification is unstoppable, yes, but its success will depend on how we manage its shadows.