-

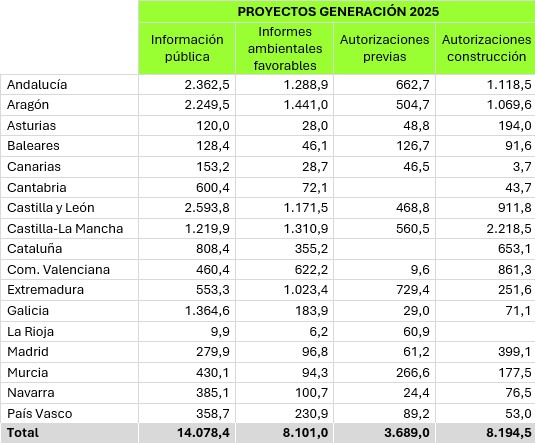

According to the latest report by Opina 360’s Renewable Energy Observatory, Spain authorized 8,194.5 MW of renewable capacity in 2025, 69% less than the previous year.

-

We have designed a system to pour energy into the grid, but not necessarily for industry to draw it where it needs it.

-

Energy must be a vector of industrial development, not just a sustainability statistic.

January 30, 2025

The energy sector often falls into the temptation of measuring the success of the green transition by weight. We count megawatts, add up hectares of solar panels, and celebrate every administrative authorization as if it were a goal scored in the 90th minute. However, the latest data invite a necessary pause—a moment to lift our eyes from official gazettes and ask a key question for the competitiveness of our industry: what is the point of accelerating generation if we do not ensure the “plug” for those who are meant to consume that energy?

This week, the social research institute Opina 360 shed light on the real state of renewable permitting with the latest report from its Renewable Energy Observatory. The report concludes that Spain authorized the construction of 8,194.5 MW of renewable generation in 2025, 69% less than the year before.

At first glance, this might look like an abrupt slowdown—bad news for decarbonization. But as Juan Francisco Caro, director of Opina 360, rightly points out, this is better understood as a “return to normality” after the administrative fever of 2024, a year inflated by the urgency of meeting expiration milestones. The market stabilizes, the foam settles, and the beer remains. But it is precisely now, as the fog of mass permitting clears, that the seams of the system are exposed.

The fever of “generacentrism”

A rationalization in the pace of authorizations does not mean the underlying problem has disappeared. We remain immersed in what the Industry and Energy Forum has termed “generacentrism”: the obsessive tendency to focus public debate and policy on energy supply, while systematically ignoring demand.

In a single year, 8,194.5 MW of new capacity were authorized, the vast majority—85.6%—corresponding to photovoltaic energy. Geographically, more than half of this capacity was concentrated in three regions: Castilla-La Mancha (2,218.5 MW), Andalusia (1,118.5 MW), and Aragon (1,069.6 MW). In total, 14,078.4 MW went through public consultation, and 8,101 MW received a favorable environmental declaration. These are significant figures in terms of capacity and administrative volume. Yet while we celebrate this theoretical production capacity, the physical reality of the electricity grid tells a very different story—one of saturation and missed opportunities.

As we recently recalled at a meeting at Foment del Treball, and as acknowledged by the Director General of Energy of the Government of Catalonia, Marta Morera: “No one was thinking about demand, because all efforts were focused on generation.” We have designed a system to pour energy into the grid, but not necessarily for industry to draw it where it needs it.

Two maps that do not align: generation and demand

This is where Opina 360’s data must be cross-checked with infrastructure reality. While developers celebrate new construction permits, industrial players look with concern at the grid map.

The latest figures from the Industry and Energy Forum, prepared in collaboration with Opina 360, show that Spain’s electricity grid is at a very high level of saturation. Specifically, 85.7% of Spanish substations are saturated. In the final two months of 2025 alone, the grid lost nearly 2.8 GW of access capacity.

The territorial mismatch is striking. Entire provinces with a strong industrial tradition or potential—such as Zaragoza, Álava, or Biscay—display a “full” sign at 100% of their substations. Castilla-La Mancha, which led renewable permits in 2025 with 2,218.5 MW, saw grid saturation jump from 85.3% to 93.4% in just two months. Andalusia, second with 1,118.5 MW authorized, lost 680.9 MW of available capacity over the same period. Aragon, third in the ranking with 1,069.6 MW authorized, continues to show very high saturation levels.

The problem is not that there are too many megawatts in Galicia or too few in Aragon. The problem is that we continue to plan generation without considering where industry—the entity that must consume this energy—is located now and will be located in the future. As warned by Tamara Yagüe, president of Confebask: “Without sufficient ‘plug-in’ capacity, we neither grow nor make progress in the energy transition.” It is of little use for a developer to have permission to build a photovoltaic plant in Castilla-La Mancha if the industry that needs to decarbonize in the north or along the Mediterranean coast lacks the physical capacity to increase its contracted power.

Storage is advancing, but it does not replace the grid

Opina 360’s report does, however, bring one hopeful data point for industrial energy management: the rise of storage. Battery permits have tripled, and there is a flood of projects under review totaling 6,553.8 MW—215% more than in 2024.

This is music to the ears of industrial energy managers. Storage is the key that allows renewable volatility to be transformed into a reliable baseload for a factory. Yet once again, we return to square one: no matter how large it is, a battery needs to connect to the grid to charge and discharge. If the substation is saturated, the battery remains a paper project, unable to contribute to the company’s competitiveness.

The energy transition cannot be a generation monologue

Opina 360’s data show that the renewable permitting system remains active, that projects exist at every administrative stage, and that storage is beginning to take off strongly. This dynamism is undoubtedly a positive sign. However, when these authorizations are not aligned with real grid access capacity or with industrial demand needs, the result is an energetically unbalanced and territorially asymmetric system.

The energy transition cannot be a monologue of generation alone. It must place industrial energy management at its core, ensuring that new megawatts are not only produced, but delivered where they are needed and under conditions that sustain productive activity. The availability of firm, accessible, and competitively priced energy at the point of supply is now a determining factor in reindustrialization.

The normalization in permitting pace seen in 2025 opens a window of opportunity to correct course. It is no longer just about how many megawatts are authorized, but where and for what purpose. Overcoming generacentrism and planning the grid with an industrial vision is not a strategic option—it is a structural necessity. Otherwise, we risk building an energy system that looks highly advanced on paper but fails to translate into real competitiveness. Energy must be a vector of industrial development, not merely a sustainability statistic.